Could the sun be invisible?

I went down a rabbit hole recently, pondering the question:

Assuming a species has evolved eyes, could they evolve in such a way that the sun is invisible?

There are a few more assumptions needed here, like the sun being the primary source of heat/energy for the celestial body that the species is evolving on, etc. Let's just say it's a species evolving on Earth.

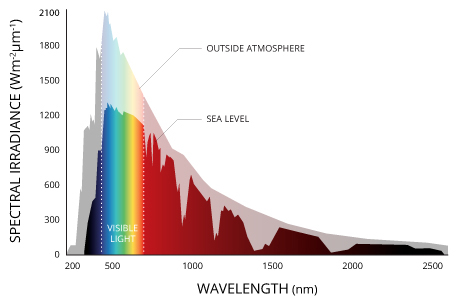

Below is a graph[1] of our sun's radiation spectrum:

We can see that the visible part of the spectrum aligns with the peak area of the specturm. In fact the source[1] actually has a short snippet about this:

Predators would not be able to efficiently hunt prey without light from the sun and prey would not be able to take advantage of dark areas if predators were adapted to dark habitats. Human eyes are adapted to the visible spectrum, though some other species can see ultraviolet light in addition to colors.

Tangent: Why isn't the sky purple?

Contrary to popular belief, the sky is not blue because of the ozone in the stratosphere. The sky appears blue due to the scattering of all wavelengths of light by all gases in the atmosphere. This is known as diffuse sky radiation. I'll let let Wikipedia explain:

The dominant radiative scattering processes in the atmosphere are Rayleigh scattering and Mie scattering; they are elastic, meaning that a photon of light can be deviated from its path without being absorbed and without changing wavelength.

Earth's atmosphere scatters short-wavelength light more efficiently than that of longer wavelengths. Because its wavelengths are shorter, blue light is more strongly scattered than the longer-wavelength lights, red or green. Hence, the result that when looking at the sky away from the direct incident sunlight, the human eye perceives the sky to be blue.

So if short-wavelength light is scattered more efficiently, and the shortest wavelength the human eye can perceive is violet, not blue, why isn't the sky violet? (Naturally, there's an xkcd for this.)

It turns out the sky isn't violet because of the way our eyes have evolved[2]:

We have three types of colour receptors, or cones, in our retina. They are called red, blue and green because they respond most strongly to light at those wavelengths. As they are stimulated in different proportions, our visual system constructs the colours we see.

When we look up at the sky, the red cones respond to the small amount of scattered red light, but also less strongly to orange and yellow wavelengths. The green cones respond to yellow and the more strongly scattered green and green-blue wavelengths. The blue cones are stimulated by colours near blue wavelengths, which are very strongly scattered. If there were no indigo and violet in the spectrum, the sky would appear blue with a slight green tinge. But the most strongly scattered indigo and violet wavelengths stimulate the red cones slightly as well as the blue, which is why these colours appear blue with an added red tinge. The net effect is that the red and green cones are stimulated about equally by the light from the sky, while the blue is stimulated more strongly. This combination accounts for the pale sky blue colour.

It may not be a coincidence that our vision is adjusted to see the sky as a pure hue. We have evolved to fit in with our environment; and the ability to separate natural colours most clearly is probably a survival advantage.

Return

Now we return to the original question: could eyes evolve in such a way that the sun is invisible?

Among species with eyes, it seems reasonable to assume that those who see more wavelengths of light probably have a survival advantage over those who see fewer. Imagine if we could only see colours at the red end of the visible spectrum - we'd be missing out on a lot of the world. But what if we were missing out on the whole world of colour? What if our eyes - those rods and cones - evolved differently?

And now we have to stop, because if eyes cannot see any wavelengths emitted by the sun, can we still call them eyes?

I think the answer is no. And therefore my original question is poorly formed.

We understand "eyes" and "vision" specifically in relation to the visible spectrum of a sun or light source. We actually have another sense that can detect the infrared radiation from the sun (touch) - it tells our body how warm it is. We don't descibe that as 'vision', and we don't think of it as 'seeing' heat.

So I've basically nerd sniped myself. The sun can't be invisible for any species with sight, because our definitions of "eyes" and "sight" directly depend on that source of light.

Seems I need a more robust mental model for thinking about the senses.

Sources

[1] Fondriest Environmental, Inc. “Solar Radiation and Photosynethically Active Radiation.” Fundamentals of Environmental Measurements. 21 Mar. 2014. Web. < https://www.fondriest.com/environmental-measurements/parameters/weather/solar-radiation/ >.

[2] Philip Gibbs “Why is the sky blue?” UC Riverside. May 1997. Web. < https://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/General/BlueSky/blue_sky.html >

(No, I don't remember how to do references properly, but I think that covers everything.)